As investors, we like to pride ourselves on our highly analytic and well-informed minds. We arm ourselves to the teeth with a plethora of charts and whatever other data sources we can wrangle up. We maintain a keen awareness of the latest news and current affairs. And we have the theories to assimilate all of this information into useful buy and sell signals.

Perhaps we even work on mental toughness. We read books about investor psychology. If you’re one of the slightly more new-age amongst us, you might even practice meditation to clear the mind of other stresses. Whatever it takes to turn our feeble human minds into cold, calculating machines built to make impeccable investment decisions. But just how successful at this game are we?

A blast from the past

In the transcription of a lecture found in his 1963 book Conjectures and Refutations, the highly influential philosopher of science, Karl Poper, provides a forceful example of what we now know as confirmation bias. In it, he narrates an anecdote about a correspondence he had with Alfred Adler, founder of the school of individual psychology.

The correspondence begins with Popper reporting a case to Adler that he did not find particularly “Adlerian.” That is to say, it did not seem to fit well with Adler’s theories at the time. But, apparently, Adler had no trouble absorbing the case within his theoretical framework.

Somewhat shocked by this, Popper wrote back, asking how Adler could be so sure. To this, Adler replied with a simple “because of my thousandfold experience.” To which Popper replied, “and with this new case, I suppose, your experience has become thousand-and-one-fold.”

Even trained minds fall into easy traps

The point Popper is trying to get across in his lecture shouldn’t be too hard to divine from this little anecdote. It’s a classic case of confirmation bias: that tendency of the human mind to filter information and interpret it according to an already-internalized belief system.

What is so forceful about Popper’s lecture, however, are the subjects he speaks of. His lecture is not a report on some cute number sequence guessing game (Peter Wason’s famous experiment in which the first recognized description of confirmation bias is thought to be found). Nor is it a simplistic look at the easily-derided believers in far-out theories, like flat-earthers. It’s not even a look at how the general population will seek out information and explain events in line with political and moral predispositions.

Rather, it’s a cold harsh look at the minds of those who should know better—his academic peers. By drawing his conclusions from an observation of the minds trained in academic rigor, he illustrates just how blind we can really be to our own biases.

Investing is about numbers and the numbers never lie…

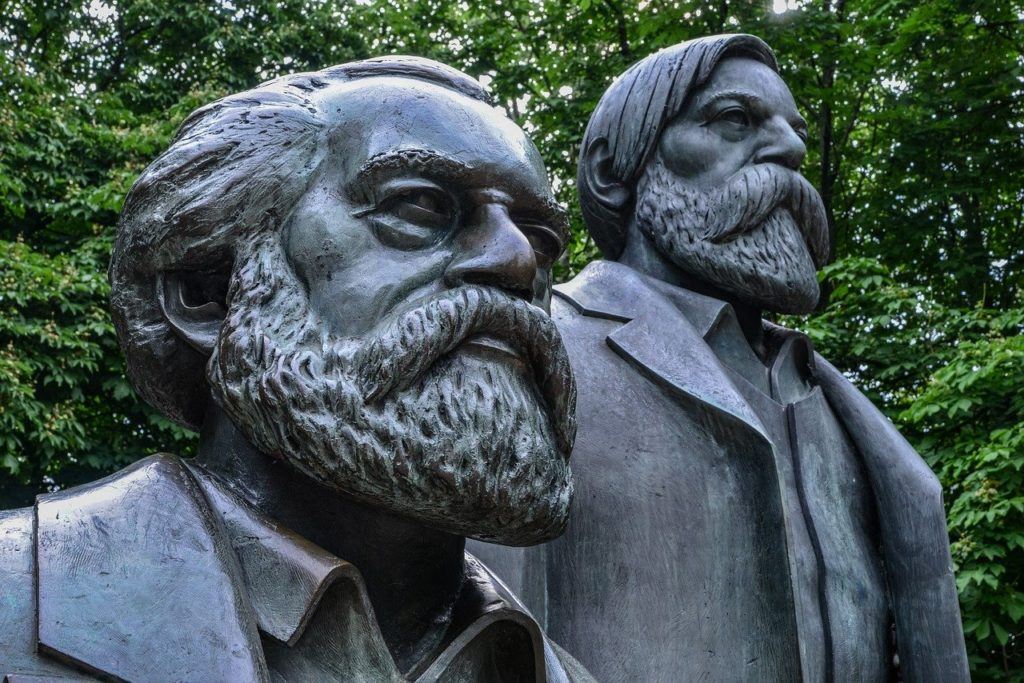

For those who have read the lecture, your first remark might be that there is a heavy focus on the ideas of Marx, Freud, and Adler. Given that many of these thinkers’ ideas have now degraded to the point of becoming memes, we might be tempted to arrogantly presume that we’re immune to such folly in our thinking. And besides, we’re not liberal arts students with majors in; we’re investors, we have numbers, and numbers never lie!

But what can we say about fields of study like nutrition science and economics? Even with decades of refinements in our scientific methods and access to an abundance of data, debates still rage on. The healthiest diet in the world will also kill you. And, apparently, governments should step in to regulate the business cycle, but they should also be as hands-off as possible. You know, numbers: they never lie.

How do theories backed by numbers come into conflict?

So if doggedly held beliefs that are in conflict with each other exist, even in modern, data-driven fields of study, what is going on, and how do we avoid this trap? Putting aside the inevitable uncertainty that’s bound to occur in systems as complex as the human body and the modern economy, for a moment, one answer is offered up by Popper: refutation.

What refutation implies is that a theory should be falsifiable if certain events occur. If I, as an investor, say that bull markets always occur in November, then a bear market occurring in November is an outright refutation of my theory. To Popper, “every ‘good’ scientific theory is a prohibition: it forbids certain things to happen.” Seems simple enough, yes?

Irrefutability and the revisionist two-step

While refutation is a simple concept to grasp, it is not always so easily put into practice. Problems occur when a theory is made irrefutable. A theory can be said to be irrefutable if it is either formulated in such a general manner that it does not sufficiently prohibit anything—thus becoming untestable—or it is modified to explain away refutations.

Examples of these sorts of theories provided by Popper are Marxism and astrology. In the case of astrology, it almost goes without saying that its vague and non-specific predictions do not lend themselves well to refutation. And as for Marxist theories, Popper acknowledges that they were, at first, scientifically postulated. However, when their predictions did not play out as expected, revisions and reinterpretations saving them from refutation turned them into dogmatic and irrefutable theories.

Investing theories and Marxist revisionism

There’s a popular myth that has endured for eons: that republicans are good for the stock market. You would think that the persistence of this theory would imply that it is true given the simplicity of both its formulation and tests for refutation. Yet, a quick look at history reveals that the theory couldn’t be further from the truth.

So how has this theory persisted? Simple. Investors are like Marxists. The theory is saved from refutation through a series of ad hoc additions and revisions; “Republicans are good for business because of tax cuts and business-friendly policy…” “don’t forget the dot-com bubble that helped Clinton’s record and hurt Bush…” “and the housing crisis…” This list goes on.

Don’t be a Marxist: accept refutation

The world is a complex place and, as investors, we rely on theories that help make sense of it all. Worrying about the composition of indexes, federal bank monetary policies, impending investment bubbles, and all the other things that go bump in the night hardly seems worth it. When a simple platitude comes along, seemingly capturing it all, it can be seductive and hard to let go of; often, it’s easier to revise it to the point of irrefutability than it is to divorce ourselves from it. So before you “buy low, sell high,” bend it like Buffett, or whatever else it is you do, ask yourself if you’re theory actually holds up, or if you’re just being a Marxist and making excuses for it.

—

(Featured Image by wal_172619 on Pixabay)

DISCLAIMER: This article was written by a third party contributor and does not reflect the opinion of CAStocks, its management, staff or its associates. Please review our disclaimer for more information.

This article may include forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements generally are identified by the words “believe,” “project,” “estimate,” “become,” “plan,” “will,” and similar expressions. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks as well as uncertainties, including those discussed in the following cautionary statements and elsewhere in this article and on this site. Although the Company may believe that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, the actual results that the Company may achieve may differ materially from any forward-looking statements, which reflect the opinions of the management of the Company only as of the date hereof. Additionally, please make sure to read these important disclosures.